-

Africa’s Gaming Market and the post Covid-19 era

While Africa has avoided as devastating an impact from novel coronavirus (Covid-19) as Europe, North America and Asia, its effects…

0 -

FRAMEWORK FOR THE REGULATION OF THE NIGERIAN CRYPTO ASSETS MARKET

1. INTRODUCTION It is undeniable that there is a Nigerian Crypto Assets Market (“Crypto Assets Market”), which is part of the…

-

Lagos to become Las Vegas of Africa

Global Gaming Africa has announced plans to co-host the maiden Lagos International Poker Tournament as part of an initiative to…

-

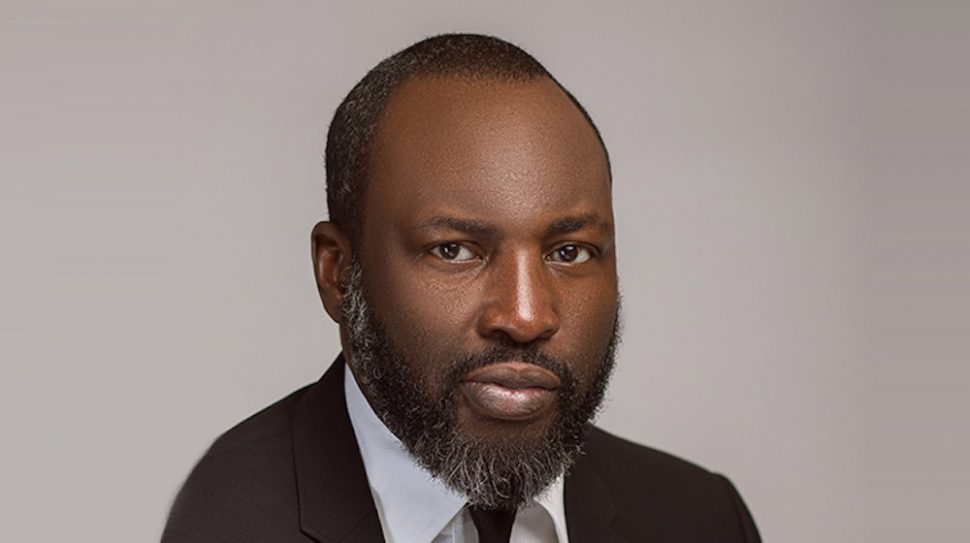

Maikori: With ICE Africa, gaming will never be the same

With the maiden edition of ICE Africa proving a resolute success, Yahaya Maikori, partner at Law Allianz and founder of…

-

ICE Africa Champion Yahaya Maikori shines a light on the industry

For the second edition of ICE Africa this October, Clarion Gaming has launched a new initiative designed to champion key…

-

AFRICA REGULATORY ROUND-UP – IS THERE A CASE FOR A PAN-AFRICAN GAMING REGULATION?

As the African market continues to attract the attention of international operators, there is a growing demand for pan-African regulation,…

-

African Regulatory Round-up: Pan-African Regulation

As the African market continues to attract the attention of international operators, there is a growing demand for pan-African regulation,…

-

Maikori: A guide on how to secure an African partner

It is universally accepted, writes Yahaya Maikori, gaming lawyer at Lagos-based Law Allianz, that for any business to thrive in a…

-

African Regulatory Round-up: Building a Picture of the Legal Landscape

In the second part of his deep dive into key regulatory reforms being made in a number of African jurisdictions,…

-

OVERVIEW OF COMPARATIVE STANDARDS FOR PROTECTION OF TRADEMARKS

1. Introduction Any international discussion of trademarks protection regime today must stem from the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual…

Articles

Law Allianz > Articles